The Price We Pay for Pain

Suffering as a Service

Reading time approx. 5 minutes

When We Pay to Struggle

It all started with a burpee. A friend had dared me to join a new fitness program that promised not just results but transformation—at a cost. “It’s not about getting in shape,” the coach announced on day one, his voice equal parts encouragement and menace. “It’s about embracing the pain.”

By week three, I was hooked. Not because I enjoyed the workouts (they were grueling) or because I saw results (I hadn’t yet), but because I needed to believe that my suffering had purpose. Each squat, each push-up, and every ounce of soreness the next day was proof I was doing something meaningful. “No pain, no gain,” they said. I bought it, along with a premium subscription for personalized agony.

This was the same logic that led me to choose a rugged mountain trek for vacation instead of a relaxing beach. I paid a small fortune for blistered feet and altitude sickness, all because the journey promised a “sense of accomplishment.” It made me wonder: why do we willingly pay for suffering, even glamorize it? From boutique spin classes to “hardcore” travel adventures, there’s an entire economy that profits from turning hardship into a luxury.

Later, I found myself scanning social media for validation. Photos of muddy shoes after a Spartan Race or the sweaty aftermath of a CrossFit session weren’t just posts—they were badges of honor. The harder it looked, the more admiration it received. And I couldn’t deny how good that validation felt.

What struck me most was this: I wasn’t alone. Many of us seem to crave these controlled forms of hardship. Suffering isn’t just tolerated; it’s marketed and sold. But as I reflected, I wondered: when does the quest for meaningful struggle become self-inflicted punishment?

How Does It Work? Science, Baby!

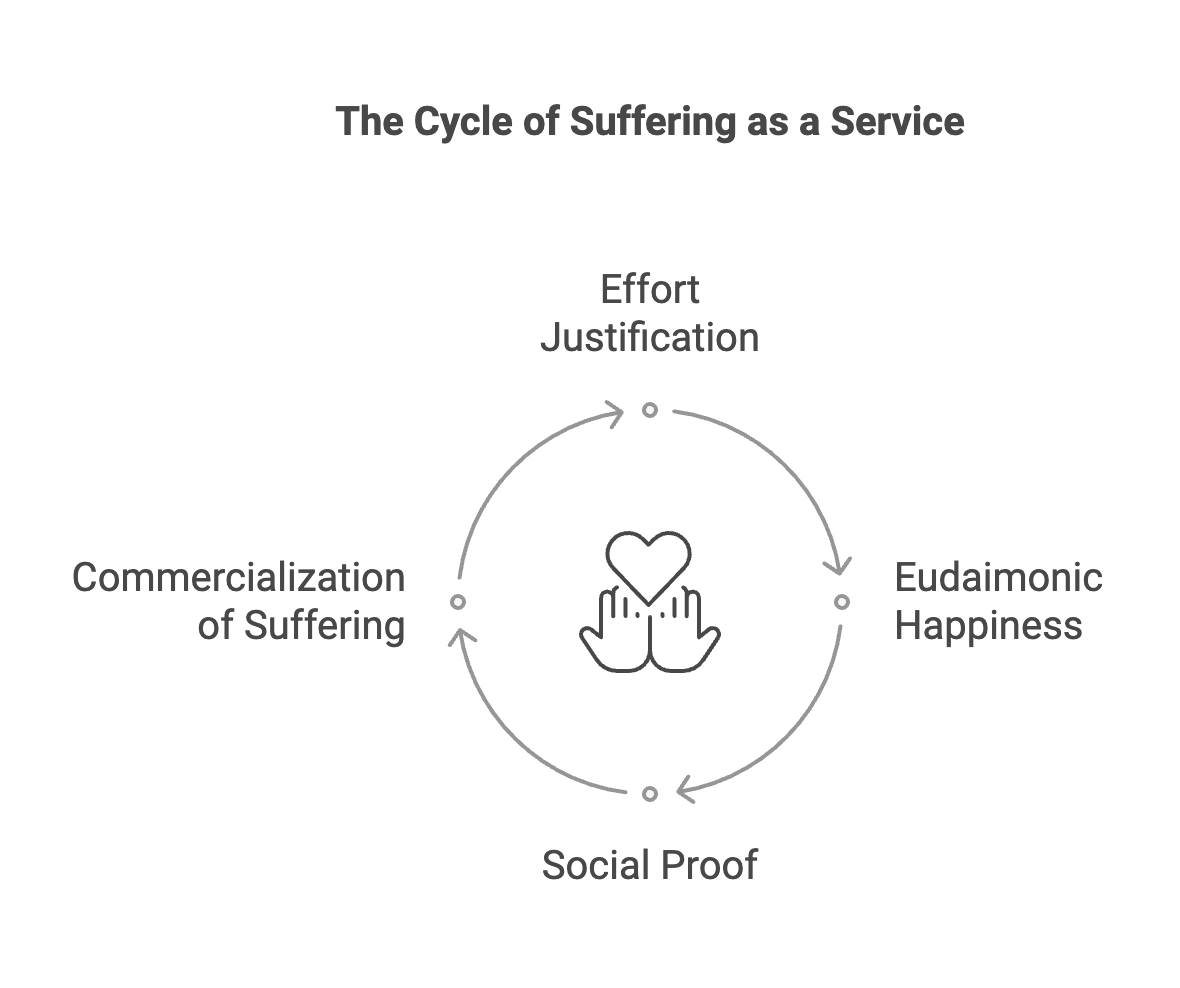

The phenomenon of “Suffering as a Service” is deeply rooted in psychology, specifically in the concepts of effort justification and the eudaimonic pursuit of happiness. Effort justification, a principle from cognitive dissonance theory, explains why we value things more when they require greater effort. When we invest time, money, or physical pain, our brains rationalize the experience to avoid the uncomfortable thought that our suffering might have been unnecessary.

On a deeper level, the trend ties into the human desire for eudaimonic happiness—a sense of fulfillment derived from purpose and growth rather than mere pleasure. Unlike hedonic happiness (seeking comfort and ease), eudaimonia often involves effort, challenge, and even struggle. It’s the reason people endure marathons, climb mountains, or willingly embrace Spartan-like challenges.

Social proof also plays a role. When we see others glorify their struggles, we’re more likely to adopt similar behaviors, believing they lead to social recognition and personal growth. Platforms like Instagram amplify this effect, showcasing a curated version of hardship that seems both aspirational and rewarding.

Finally, the commercialization of suffering taps into status signaling. Expensive personal trainers, extreme fitness challenges, and grueling travel adventures aren’t just hardships—they’re symbols of privilege and commitment. We’re not just paying to suffer; we’re paying to tell the world that we can afford to suffer stylishly.

Why This Is Important?

The Psychology:

“Suffering as a Service” capitalizes on effort justification and our pursuit of eudaemonic happiness. We value things more when they’re hard-won, rationalizing pain as a marker of worth. Social proof and status signaling fuel the trend, turning hardship into a symbol of personal growth and success.

Why It Matters:

Imagine you’re at a crossroads, debating whether to invest in a grueling boot camp that promises transformation. You hesitate—not because of the cost but because of the discomfort. Yet the testimonials, the curated success stories, and the allure of proving yourself draw you in. This isn’t just a financial decision; it’s an emotional one, tied to our deepest insecurities and aspirations.

The issue arises when this pursuit becomes exploitative. Marketers know we equate pain with progress, and they’ve built an industry to capitalize on our vulnerability. The promise of meaning and transformation is seductive, but it can also lead to burnout, disillusionment, or even financial strain.

Moreover, this phenomenon perpetuates a flawed narrative: that struggle is the only path to worthiness. It dismisses the value of rest, simplicity, and joy. Not every achievement needs to be earned through hardship, yet we’re conditioned to believe otherwise.

By understanding the psychology behind “Suffering as a Service,” we can question whether the pain we pursue is truly meaningful or simply a product of clever marketing. It’s not about avoiding struggle but choosing it intentionally, ensuring it aligns with our values and goals rather than external validation.

And Now?

Before you sign up for the next “life-changing” challenge, pause and ask: What am I really trying to achieve? If it’s growth, consider whether the struggle aligns with your values—or if it’s just a shiny badge of honor. Try embracing simpler forms of fulfillment, like learning a new skill without publicizing it or prioritizing rest without guilt.

Seek balance by choosing your hardships wisely. Not all suffering is created equal, and not all of it leads to growth. Reflect on whether the pain serves a purpose or simply feeds a narrative. The most meaningful journeys often involve both effort and ease.

Bottom Line

We’re drawn to paid suffering because it feels purposeful, but not all pain is worth the price.

Checklist:

Pause: Am I choosing this challenge, or is it choosing me?

Align: Does this struggle align with my values and goals?

Question: Am I paying for growth or external validation?

Reflect: Is this hardship balanced by moments of joy and ease?

Decide: Will this experience leave me truly fulfilled—or just exhausted?

Chief Behavioral Officer wanted

Where are management decisions made every day that are still based on people acting logically? Where can you be a Chief Behavioral Officer yourself this week?

See you next Tuesday.

If you would like to send us any tips or feedback, please email us at redaktion@cbo.news. Thank you very much.